An Analysis of Mozart's Fantasy in C Minor K. 475

Background

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is a classical composer who lived from 1756 to 1791. Despite his short life, he produced numerous works with great acclaim from many other composers during his time.

With respect to his piano solo works, Mozart seldom wrote pieces in the minor key. He wrote two piano sonatas in the minor key, and each holds significance historically to his life. His Sonata in A Minor K. 310 was written as a response to his mother's death, and his Sonata in C Minor K. 457, which was paired with the Fantasy K. 475, was written as a response to his epiphanic discoveries while studying Bach's works such as The Musical Offering BWV 1079, some of J.S. Bach’s works “that struck Mozart like a bolt of lightning” (Sigerson 68).

With almost all of his works, Mozart adheres to classicism. He writes in a style that is familiar to us as classical style–alberti bass and homophonic texture to name a few examples. Rarely does he break out of this style, and as such, attention must be paid when he chooses to do so.

A simple timeline of Mozart’s life in relation to the aforementioned events is given as a figure below.

- 1756 | Mozart’s birth.

- 1778 | Mozart’s mother passes away.

- Piano Sonata No. 8 in A minor, K. 310/300d (Paris, Summer 1778)

- 1782 | Deep study of J.S. Bach’s works.

- Fantasy No. 1 with Fugue in C major, K. 394 (Vienna, 1782)

- Fantasy No. 2 in C minor, K. 396 (Vienna, 1782)

- Fantasy No. 3 in D minor, K. 397 (Vienna, 1782)

- 1784 | “Dedication copy” containing only the sonata, written by a Viennese scribe.

- Piano Sonata No. 14 in C minor, K. 457 (Vienna, October 14, 1784)

- 1785 | Official publishing of K. 457/K. 475.

- Fantasy No. 4 in C minor, K. 475 (Vienna, May 20, 1785)

- 1791 | Death of Mozart.

With this timeline, we can see that the study of Bach’s works influenced the creation of many consecutive fantasies, and the first is accompanied with a fugue–a direct allusion to Bach’s fantasy and fugue. We can also note that K. 457 and K. 475 were published together as a single opus (Irving). With the fantasy preceding the sonata despite the sonata’s earlier creation, we can trivially observe Mozart’s attempt to allude to the baroque fantasy and fugue format. This is especially true when we consider that some of the ideas in the sonata are contained in the fantasy and expanded upon.

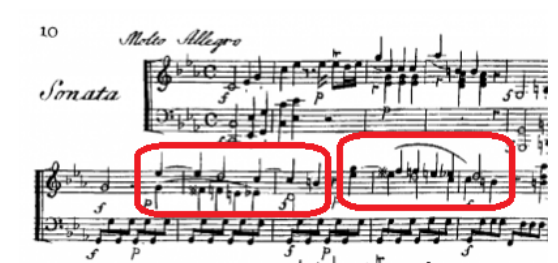

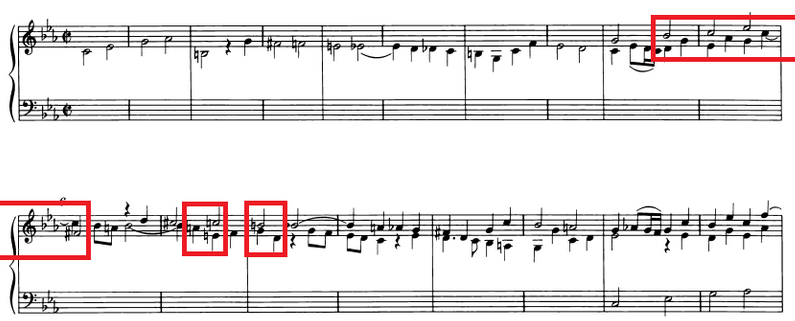

The above is an image of the Eb, F#, G, and Ab in the Sonata 3rd movement, which is a pivotal part of the exposition of the fantasy.

We can also observe some of Mozart’s employment of polyphonic counterpoint, which is very unusual of Mozart, especially when compared to his earlier works.

Form

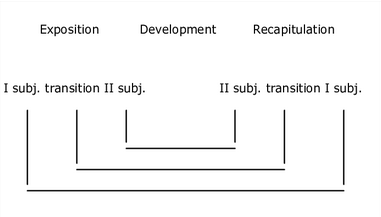

In the Fantasy, there are five boldly labeled sections with tempo markings. We can view these as sections because of the large separation of the systems in the music and also the large contrast of tempo between each two sections. As such, if the fantasy were to be converted to a sonata form, it would become the mirror recapitulation form (Mladjenović).

From this, we can generalize sections from the fantasy and appropriate them to the sonata recapitulation form.

- Adagio

- Measures 1-18

- C minor

- 1st Subject

- Measures 18-25

- B minor/G major

- Transition

- Measures 26-41

- D major

- 2nd subject

- Measures 1-18

- Allegro

- A minor/Modulations

- Development

- Andantino

- Recapitulation of the 2nd subject

- Bb major

- Piu Allegro

- Transition

- G minor/Modulations

- Tempo Primo

- Recapitulation of the 1st subject/Coda

- C minor

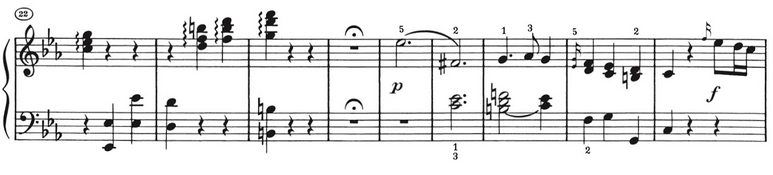

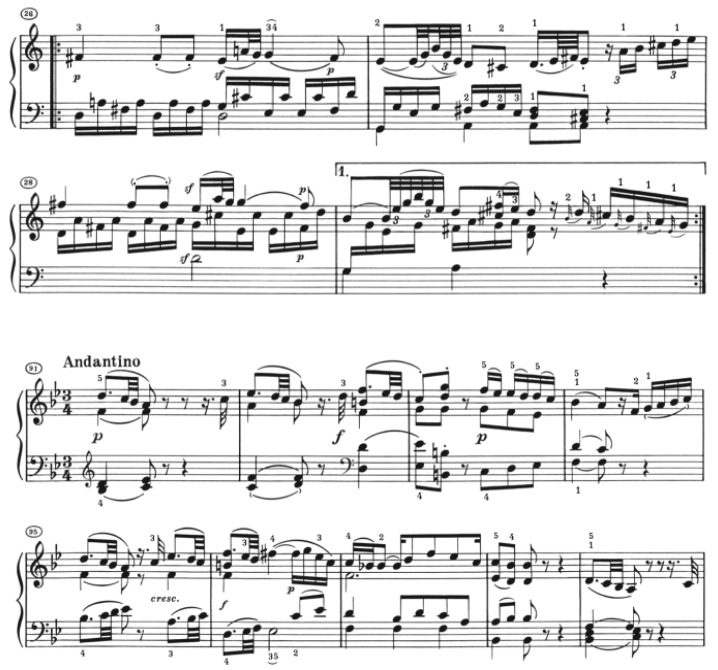

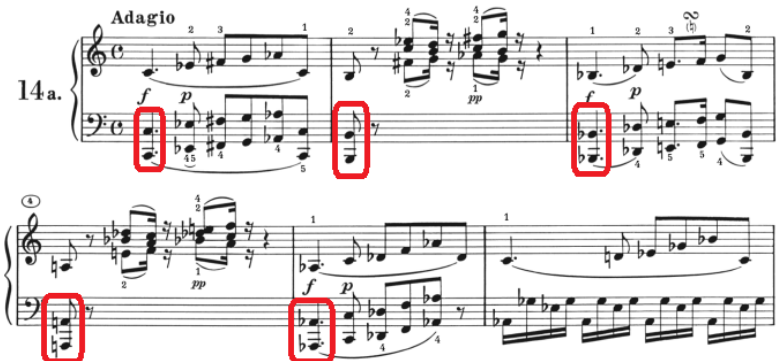

Below are figures of the theoretical second subject and its corresponding recapitulation of the Andantino movement. The dotted eighth followed by the two thirty-second notes are reminiscent of the sixteenth thirty-second notes.

Another consideration of this hypothetical sonata form is the length of the first exposition in comparison to the recapitulation. As it is labeled a fantasy, there is not necessarily a form. However, it is arguable that Mozart, despite the freeform nature of a fantasy, desired a sense of symmetry, thereby leading to a design of a mirrored form. Upon a closer look, we can see that the recapitulation consists of fragmented echoes of the motifs in the exposition. We will later discover that motifs play a gargantuan role in this Fantasy, which further cements the idea that the mirrored form was by structural design.

Analysis

Adagio

Immediately, we have an oddity with the key signature. Although this piece is titled Fantasy in C Minor, the performer is not given a key signature. However, the reason for this becomes clear as more of the piece is observed.

In measure 1, we see a firm C note in forte that should resonate throughout the slurred measure, suggesting the harmony of the entire measure is rooted in C. Yet, we see a Eb, F#, and Ab in the same measure. This already creates the impression of a minor key, yet when the F# is played, our mind instinctively hears diminished. Yet we must overcome our instincts to hear the next note of G natural as it should be heard. Since the C comes so strongly in the beginning and is included in the slur with the rest of the measure, we know that the harmony has not changed. We have not moved from C diminished to major, nor is it like Mozart to abuse the harmony in this way, as Mozart requires the delivery of “every note, turn, &c., correctly and decidedly, and with appropriate expression and taste” (Jahn). With performing ideals such as these, there should be no reason for the C diminished harmony to be muddied with a G. Another point is that the F# is written as a F# rather than the enharmonic equivalent Gb. With all of these points, it becomes clear that the F# is a part of the overall harmony rather than a tension and release. Therefore, we must observe this raised 4th as a Lydian mode set in minor.

This begs the question, what inspired Mozart to experiment with the Lydian mode? To answer this question, we must refer back to the timeline and the other creations of his fantasy. When we refer back to Bach’s A Musical Offering, we can see that as the second voice enters in measures 9-11, the first voice uses a sequence of ascending fourths, and then measure 11, begins the sequence of descending fourths, starting with the Lydian interval C-F#.

As we further analyze Mozart’s Fantasy, we will see that almost all of the musical development is centered on this Lydian 4th interval. This method of using motivic development is not unique to just Mozart. In fact, Josef Haydn pioneered this style of composition, and Beethoven utilized it prolifically during the composition of his 5th symphony. Additionally, it is an interesting coincidence that all of these–Mozart’s Fantasy, Bach’s Ricercar, and Beethoven’s 5th–share the exposition key of C minor (except Mozart’s Fantasy has an additional raised 4th).

Another commonly recurring theme in this Fantasy is the chromatic descent. We see the chromatic descent in the Recercar in measures 3-5, and also in the Sonata in measures 9-11. Then we see it as a harmonic progression on the first beat of every measure in the bass section from measures 1 to 5.

Indeed, this is the second motif used by Mozart to develop this Fantasy.

Allegro

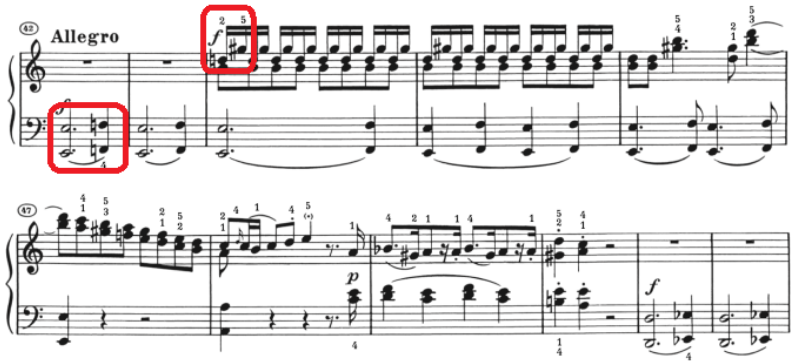

In the assumed mirror recapitulation form structure, this section is where the development of the exposition takes place. Now that we have our Lydian 4ths and chromatic sequence introduced, we can explore some of the novelties presented here.

In this section, traditionally harmony dictates that the start of the tonic key is in A minor as it appears in measure 48 before it begins to modulate, yet this is not so obvious when we consider the last measure that comes before this introduction.

Since the last harmony before the introduction of the second section is a B dominant chord, our ears are attuned to expecting Some form of E major or minor, yet we are contradicted by a F natural. To muddy the waters even further, a D and G# Lydian interval is played on top of this. Yet our traditional harmony theory prevails when we consider the D and G# as the dominant 7th and major 3rd with a lowered 2nd. Indeed, all of these unexpected resolutions give us a sense of an unsettling, unpredictable adventure, which is clearly the case with the introduction of a minor Lydian scale in the beginning: who in the classical period would expect such a modality where major and minor were the norm? The inspiration clearly comes from the study of Bach’s chromaticism, which did not match the gallant style prevalent during the baroque era.

The grand sequence starting with measures 79 is the largest sequence of chromatic bass notes, spanning a full octave. Also note the continued usage of the Lydian motif in the right hand melody during this sequence.

Andantino

The Andantino section is a reprieve from the high tension and chromatic Allegro movement. Here the harmony is sweet and pastoral with minor miniature tension.

Notice the continued usage of the intervallic motif in the right hand as the D descends to an A. This time, to achieve the calm before the stormy Piu Allegro section, Mozart decides to finally pick a key to stay diatonic and in the major key throughout the section.

The dotted 8th and the 32nd notes are reminiscent of the second theme of the mirrored form.

Piu Allegro

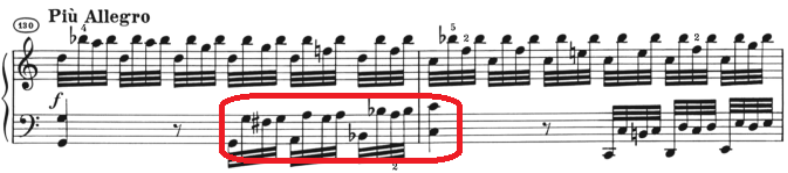

If we refer back to the transitory section of the first Adagio movement, we notice that it consists of fast repeated notes along with 32nd note bursts. This matches the spirit of the Piu Allegro section.

In this fiery section, the circle of fifths are explored, but upward diatonically to continue the usage of the motivic 4th interval throughout the piece.

As this pattern of intervals continues, the time period between the intervals shortens and more 4ths appear as the music cycles through many modes before reaching the conclusion by recapitulating the opening. This, in a sense, is a form of achieving symmetry and a sense of completion before resolving back to the first theme.

Conclusion

This behemothic work is indeed an exploration of Mozart’s discoveries of motivic composition and the color palette of music through the use of modalism and chromaticism. It is a reflection of Bach’s composition method as he used in The Musical Offering, applying it on a modern work.

Sources

Irving, John. Mozart's Piano Sonatas: Contexts, Sources, Style. Cambridge [England] ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Jahn, Otto. Life of Mozart / By Otto Jahn ; Translated From the German By Pauline D. Townsend, With a Preface By George Grove. New York: E. F. Kalmus, 1968.

Mladjenović, Tijana Popović. “W. A. Mozart’s Phantasie in C Minor, K. 475: The Pillars of Musical Structure and Emotional Response.” Journal of Interdisciplinary Music Studies, vol. 3, no. 1-2, 2009, pp. 95–117

Sigerson, John. “W.A. Mozart’s Fantasy in C Minor, K. 475, and the Generalization of the Lydian Principle through Motivic Thorough-Composition.” Executive Intelligence Review, vol. 25, no. 35, 4 Sept. 1998.